A literate celebration of this influential Javanese woman, educator, feminist, advocate, reader/writer

Today, April 21, is Kartini Day – Selamat Hari Kartini 🇲🇨 – a day when Indonesians celebrate the influence that a young Javanese woman, daughter of a regent, had on women’s rights and education. Because her legacy has been used by different Indonesian leaders over the years to convey messages supporting both an empowering feminist perspective and one that serves to keep women in their homes and bound to traditions, I prefer to draw my inspiration directly from Kartini’s own words. So, while many Indonesian women/girls dress up in traditional, ornate Javanese costumes – kebaya – and gather for formal ceremonies in schools and other settings to celebrate Kartini’s impact, today, I honor her commitment to literacy and education by crafting this celebratory post.

“I have always been an enemy of formality. I am happy only when I can throw the burden of Javanese etiquette from my shoulders. The ceremonies, the little rules, that are instilled into our people are an abomination to me.”

As part of the work that Puji and I continue to do to make sense of our collaboration, we have both been reading Letters of a Javanese Princess (English version available free here), a collection of Kartini’s letters published and translated (from her original Dutch writing to overseas friends) after her death. All of the quotes I share in this post come from this text. From these letters, we get glimpses into what Kartini stood for and how she felt about issues ranging from traditional Javanese customs confining women to language learning and the pros and cons of cultural exchange with Western civilization. Though I’m still learning about and from this inspiring advocate for women’s education and rights, I wanted to share just a few of the ways that her letters have resonated for me.

“Father could not foresee that the same bringing up which he gave to all of his children would have had such an effect upon one of them.“

Kartini was born on 21 April 1879 into a family connected to Central Javanese leadership/government – some have called them aristocracy, a term that Kartini seems to dismiss herself. From what I’ve gathered about her young life, her parents’ connections to Dutch colonial leaders/traders gave them a more open mind about how to raise their daughters – allowing them to attend Dutch elementary school outside of the home in Jepara – to a limited extent. So, while Kartini attended school until age 12, tradition eventually took over and she was confined to the “box” of her family home.

“I was locked up, and cut off from all communication with the outside world… I went into my prison. Four long years I spent between thick walls, without once seeing the outside world… there was one great happiness left me: the reading of Dutch books and correspondence with Dutch friends was not forbidden.”

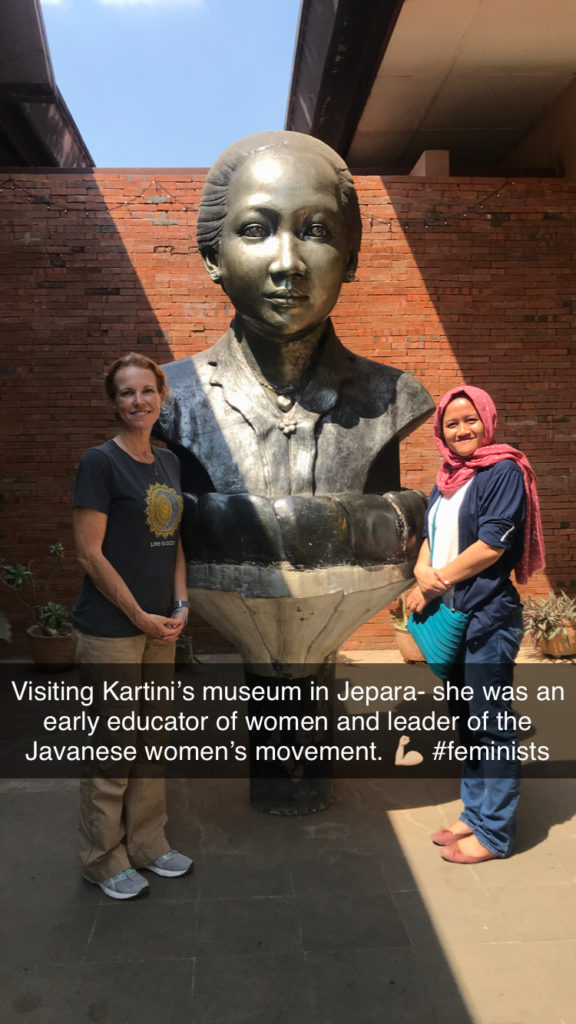

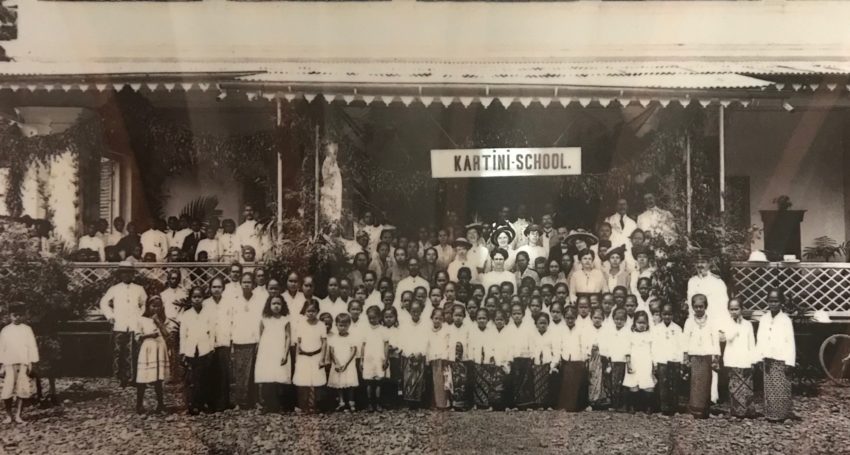

Literacy played a crucial role in Kartini’s identity development, and the reading and corresponding she did gave her access to ideas beyond the confines of her physical and cultural confines. Her story exemplifies critical literacy in action, illustrating the emancipatory and transformative potentials of reading and writing. Armed with a wider set of ideas and experiences, and bolstered by the encouragement of her European friends, once she and her younger sisters were allowed to move about the region again, Kartini became unwilling to conform to Javanese norms, to some extent. In particular, she advocated for the importance of educating women and giving them the opportunity to choose their own husbands, though she herself agreed to a marriage arranged by her father. In 1903, she became the fourth wife of the Regency Chief of Rembang. Thankfully, this husband supported Kartini’s wishes to develop schools, and the first Kartini School “opened” on the porch of the regency complex. Though Kartini Schools spread around the region and abroad, Kartini herself did not live long enough to realize her visions and see the change she set out to be in Java. Less than a year after her wedding, and just days after giving birth to her only son, Kartini died on 17 September 1904 at the age of 25.

“I fear that when once—forgive me—your Western civilization shall have obtained a foothold among us, we shall have that evil to contend with too.”

Kartini remained curious, and her letters are full of questions to her friends. She asked questions to learn about their cultures and to question the expectations and customs of her own. Deeply committed to women’s issues, Kartini wanted to learn more about the conditions women faced in other parts of the world. “Will you not tell me something of the labours, the struggles, the sentiments, of the woman of today in the Netherlands?” About marriage as a “miserable” existence for women, Kartini asked, “How can it be otherwise, when the laws have made everything for the man and nothing for the woman?”

She desperately wanted to travel outside of Java: “To go to Europe! Till my last breath that shall always be my ideal.” Growing up during the time of Dutch colonization, however, she recognized the challenges of cultural exchange and infiltration, seeing the dangers of alcohol, opium, and other “evil” that came to Java from Western influence. So, while Kartini drew from the outside to inform her thinking, her letters also reveal a cautionary approach to letting Western practices and ways of being affect Indonesian life.

“For, you see I, as a born Javanese, know all about the Indian world. A European, no matter how long he may have lived in Java and studied existing conditions, can still know nothing of the inner native life. Much that is obscure now and a riddle to Europeans, I could make clear with a few words.”

As an outsider living and learning with/from Indonesians myself, I appreciate Kartini’s reminders about the importance of both learning the local language and about conducting my research and work in partnership with locals. Currently, Puji and I are working on the first publication based on our time together in Indonesia, through which we are building an argument based, in part, on Kartini’s letters – and I couldn’t do this work without Puji’s input and guidance to help me unravel the “riddle” of “inner…life” and make things clearer to me with her words. Just like Kartini, reading and writing help me process my thinking, remain curious, advocate for change, and connect with friends. And, though I could go on and on about this inspirational woman, I will step away from this writing to return to reading her letters, leaving you with these words of wisdom from Kartini.

“…the watchword of all reformers must be Patience. We cannot hasten the course of events, we only retard them when we try to push forward too hastily. ”

Fascinating and inspirational!

Thank you for introducing me to Kartini through your blog post. As someone who was raised in the academy by mostly second wave feminists, I have spent much of the last three years growing my understanding of feminism and its intersectional and global manifestations. I can’t wait to dive into her letters. I was surprised to learn of her untimely death, but you and Puji are carrying her legacy.

It would be awesome for you and your students in your feminism courses to bring not only Kartini’s words into your discussion, but also all of the various ways that her legacy has been used/taken up by (mostly) Indonesians since her death. It is fascinating to see the narratives that get ascribed to her legacy and to examine the way that “Kartini Day” has been used, celebrated in ways that reinforce and push against dominant ideologies in that country, and how those change over time. Good stuff!