Here in Indonesia, where the overall population is reportedly about 87% Muslim (according to the CIA World Factbook page on Indonesia, which matches our findings with the secondary students who responded to our survey), I have had the opportunity to see — and hear — Islamic prayer rituals and to learn more about Muslims’ values and practices through my conversations with friends and colleagues here in Semarang. I’ve gained a greater understanding of the Islamic religion, some of their policies and practices, and the variation among Muslims in how they enact their Islamic traditions. I have had the chance to visit, and sometime enter, mosques as we’ve traveled around Indonesia.

The beautiful ceiling in the Masjid Ulul Albab Universitas Negeri Semarang – located behind the guest house I live in.

Photo taken at: Masjid Raya Mujahidin Pontianak, Kalimantan

I’ve also had the opportunity to learn more about women’s experiences within this religion, and I am thankful for all of the conversations I’ve had with Puji and her husband, my friend Karina, Indonesian feminist scholar Nelly Martin-Anatias, and others who continually shed light on the Muslim woman’s perspective. For example, after a visit to a history class where I witnessed a lecture about the New Order regime, I had discussions with friends that helped me learn about the evolution of women’s hijab wearing in Indonesia, and how hijabs have been politicized here over time. Friends have shared with me their own decision-making processes about when and why they decided to don this head covering, and how they choose to do so, whether with ninjas, hijabs, and/or headscarves. My relationships with some of these women have created connections that have facilitated enlightening discussions about their perceptions and lived experiences of their Muslim identities.

Sights and Sounds of Islamic Prayer

I came to Indonesia with only the most basic understanding of Islamic prayer, in that I knew that they prayed multiple times a day, that there was a “call to prayer”, that mats were involved, and that women prayed in separate spaces than men. Interactions with students back in Rochester meant that I knew that midday prayer on Friday was kind of a big deal, and I had some general knowledge about the month of Ramadan and its Eid celebrations at the end, especially with respect to the fasting practice and how the traditions of this time of year impacted Muslim students’ schedules. But, that was really the extent of my limited understanding before I arrived in Semarang in September.

My greatest awareness has been as a result of experiencing the call to prayer and hearing it (or not) throughout the day as I live here in Indonesia and travel in the region. I’ve come to appreciate how the rhythm of the Muslim’s day gets set by the five prayer times per day. Even for someone like me, who doesn’t pause to pray each time I hear the azan, the calls have come to signal different points in my days here in Semarang as I time my meals, walks, and naps in concert with them.

Of course, when I first moved into the guest house on the UNNES campus, it was certainly unnerving when the azan jarred me from slumber at what an American might refer to as “oh-dark-thirty” — somewhere between 3:49 and 4:22 a.m. during my time here. After all, I was definitely not used to waking before the sun. But, over time, I have come to both learn to sleep through the earliest azan, and to recognize the beauty in the chorus of Muʾaḏḏinūn I can hear from bed, and then go back to sleep. Just last week, I woke as it started and was able to record 18 minutes of the passionate criers singing out all around the area. There’s something beautiful in the conviction and urging I hear in these calls encouraging believers to come pray together.

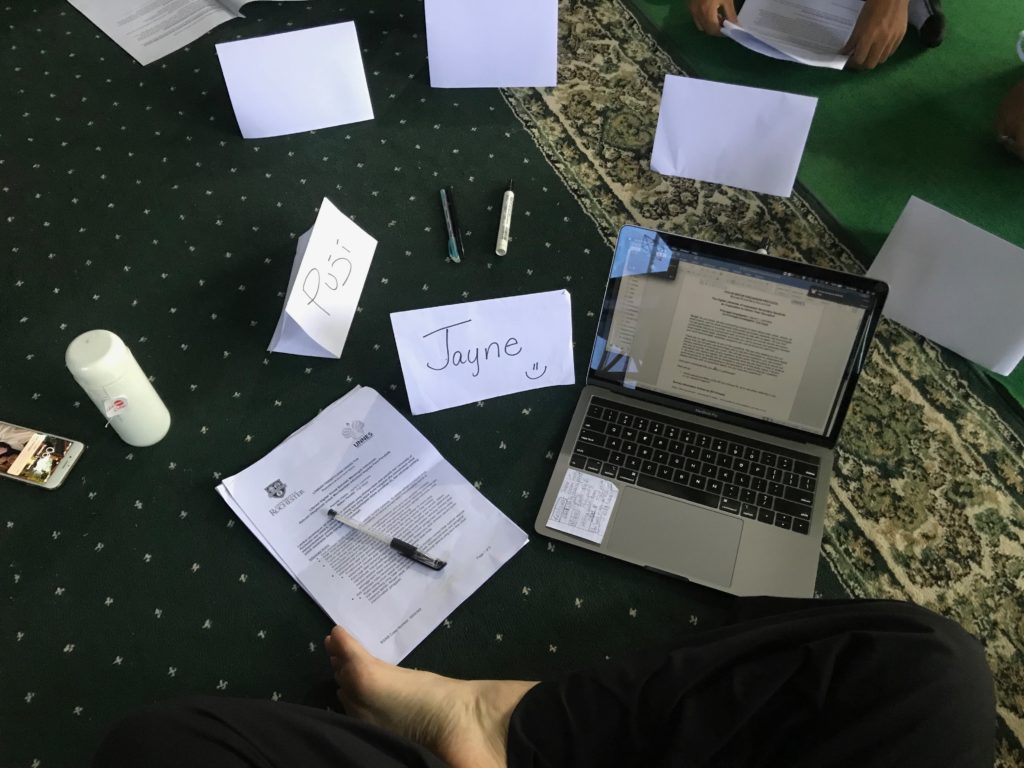

Not only have I heard these sounds signaling Islamic prayer, I have also seen the ritual in action on two occasions. Most recently, when Puji and I were conducting one of our focus groups at a high school last week, our teacher contact put us in the school mosque because it was the quietest space she could think of for us to hold and record our discussion. During the hour we spent there, male staff members and students came and went, performing silent, individual prayers while we talked to our participants about digital literacies. I felt like we were intruding, but they didn’t seem to be bothered by us being there at all.

Most significantly, in late September, Puji invited me to bear witness to her participation in the midday prayer at the campus mosque behind the guest house, the Masjid Ulul Albab Universitas Negeri Semarang. Her husband went in one direction, leading him to the large ground-floor space where the men pray (visible in the cover image for this blog post), and we went in another direction, stopping first so that Puji could perform the wudhu ritual of washing her face/mouth, arms/hands, and feet. We then ascended a few flights of stairs to a balcony area overlooking the main room of the mosque. There, Puji and three other women donned prayer dresses and laid out mats at the front of the space while I found a quiet place at the back from which I observed their lovely communion and cycles of prayer. Before we went, I repeatedly asked for assurance that it was okay for me to be there as this felt like a potential violation of a sacred space and practice. Puji assured me that not only was it more than okay for me to accompany her, but that I should also feel encouraged to take photos and record what I witnessed in order to provide a window into the practice to others. I was struck by the synchronicity and fluidity of their movements, and also by the exchange of greetings that they performed as the prayer ended. That last bit reminded me of the familiar Catholic ritual of offering each other “peace” during mass.

Author‘s Note

It feels important to note that, unlike any of my other posts from this Fulbright experience, I asked Puji to review this post before I spread it publicly. I’m very mindful of not wanting to disrespect or misrepresent the Islamic religion or people (or any religion/people, for that matter), and am sensitive to the reality that there is a great deal of misinformation, propaganda, and fear-inspiring messaging that gets spread around the U.S. about Islam and Muslims. I do not in any way want to contribute to that discourse. On the contrary, I took a long time to think about whether and how I would want to share any of what I’ve learned about this faith and its practices on my blog because I feel like it’s important to share a more representative, and thus positive, outsider’s perspective of what I’ve seen and heard. My limited experience of the Islamic religion and its practices, and my interactions with Muslim people here in Indonesia leave me with more understanding, respect, and inspiration drawn from the people who live their lives in accordance with this faith.